From Kadesh, Moses sent messengers to the king of Edom: “Thus says your brother (achicha) Israel: You know all the hardships that have befallen us…(Numbers 20:14)

But Edom answered him, “You shall not pass through us, else we will go out against you with the sword.” (20:18)

It’s Parashat Chukat (Numbers 19:1-22:1). Miriam has just died, and with her loss, the Israelites’ water source is also gone. The Midrash, playing on the fact that Miriam’s name contains the word yam (sea) in it, teaches that a magical well travelled wherever Miriam went. This loss forms the backstory for Moses’s striking of the rock at the waters of Meribah, a moment of outburst that will ultimately disqualify him from entering the Promised Land. What happens next?

In an abrupt scene change, Moses sends messengers to the Edomites asking for permission to pass through their land, a request they will reject. But note that Moses calls himself “your brother.” The word achi might just mean fellow, in which case Moses is making an appeal to common decency, but, of course, the appeal to fraternity is in some sense literal, too. The Edomites are descendants of Esau, Jacob’s twin brother. Moses has just lost a sister and identities himself as a brother. Even the fact that he says “your brother Israel” has a double meaning, since “Israel” can refer both to the nation as a whole and to the specific person, Jacob, who famously gets a name change when he wrestles with a mysterious man/angel. The juxtaposition of the scene at the waters of Meribah and the request of the Edomites is laden with a psychological force. Concealed in the request to pass through enemy land is a request for consolation, brotherhood, an appeal to connection based in shared loss.

Recall that in Genesis, Isaac and Ishmael come together to bury and mourn their father, Abraham (25:9). Jacob and Esau come together to bury and mourn their father, Isaac (Genesis 35:29). So shouldn’t their descendants come together to mourn and bury? But by this point Moses’s wish for solidarity is a fantasy. The Edomites and the Israelites may share an ancestral line, but it is too weak to hold them together. The Edomites won’t even do the Israelites the favor of letting them pass through their land. Instead of a condolence, Moses is met with arms. Who is right? The one who reaches out to establish an emotional bond and shared loyalty based in kinship or the one who retorts that kinship alone is not enough to justify alliance, that too much time has passed, anyways, and that the focus should be on geopolitical interest (“great power politics”), nothing more?

One of the striking features of collective mourning is that it seems to be both deeply political and deeply anti-political. On the one hand, mourning is political and conflictual as different groups compete to preserve the memory of the departed on their terms. They compete not just for material inheritance, but also for memory. Who gets to speak for the dead? Who really knew what old Isaac was about? His hunter son who knew how he liked the smell of game or his studious son who knew his father’s sensitivity and tenderness? But mourning is or can be anti-political in that it can be a moment of suspension, in which petty differences are put aside for the shared task of paying homage to a significant loss. In asking the Edomites for passage, Moses implicitly asks that his loss be recognized. Instead, that summons for recognition is met with callousness. Who is Miriam to us? Not only has the water dried up, but the way has also been blocked. The Israelites must go around.

The blocked passage is a metaphor for loss. Significantly, Aaron dies on Mount Hor, on the detour the people never would have taken had the Edomites allowed them entrance. If we were speculating, we might say that Aaron died of heartbreak. If we were really daring we might go further: Aaron and Moses know, on some level, that their emotional outburst at the Waters of Meribah will get them killed and they do it anyways, because they have a kind of death-wish, a momentary urge to join their sister in the next world. In a moment of weakness, these great leaders cannot bring themselves to “choose life.” Their smashing of the rock is a kind of self-demolition.

In the struggle between Moses (Jacob’s legacy) and Edom (Esau’s legacy) is a struggle not just between nations but between tendencies, one a tendency to connect, the other a tendency to repel. Aside from the specific content of the conflict, Moses vs. Edom raises a question: are funerals a time to put differences aside or a time to stress differences? The Edomites may lack compassion for the Israelites, but compassion, in the political sphere is never a neutral category, either. PR wars are often precisely about who owes compassion to whom. Can we fault the Edomites for taking extra precautions, and for not sufficiently appreciating the travail of the Israelites to which Moses appeals. If you were king of the Edomites would you let the Israelites pass? How many generations back do we need to go to find a shared ancestor?

Abraham is blessed that “all the families of the earth will be be blessed through you.” The Torah places a moral premium on familial obligation and treats empty universalism with deep skepticism (if you owe everyone the same thing, then you owe them nothing). But when does a family end and become a nation? Already in Genesis, we saw that families were anything but simple. Although Joseph and his brothers end up becoming the basis for the Israelite nation their example is hardly inspiring. Some Midrashim attest to a picture of Miriam that suggest her as someone who envied (and engaged in gossip about) Moses. Such failings do not preclude the deep love they must have felt for one another, but they do point to the complexity of that love. So what distinguishes regular national conflict from the kind of sibling conflict that we tend to think of as par for the course? Is the problem simply one of scale, or of time passing? I don’t think so.

The juxtaposition between Moses’s self-proclamation, “your brother” (which also hearkens to God’s retort to Cain, “your brother’s blood cries out to me”) and Edom’s proclamation of war highlights the intensity of Moses’s loss. Miriam is gone. Not just her specificity as a person, but also her specificity as someone beloved by Moses and Aaron. Deep love is a rarity in life. And especially for public figures, who are often known only through their personae. Miriam is one of the few people who has seen Moses from the time of birth to his later years. Moses has lost a person who sees him in this unique way. And now he appears to the Edomites as a warrior-king, the leader of a band of ex-slave nomads famed for thwarting the most powerful civilization in the region. Edom doesn’t see baby Moses. Of course, they respond as they do.

Moses is denied the path through Edom because he is denied a shortcut to his mourning, a replacement of his sister. He is taught the hard lesson that politics begins where intimacy ends and intimacy begins where politics ends. Whether he is emotionally ready to fight or not, the world won’t let him rest. Everyone mourns, but there comes a point where we mourn different losses in different ways, and this difference, though painful, though a source of bloody conflict, is the same difference that makes us individuals created not to be conformist clones of an idol, but distinctive and original variations on the ineffable.

The gap between the model of mourning in Genesis and that offered in Numbers is not just the gap between generations, but the gap between worlds. Esau and Jacob shared a world. Ishmael and Isaac shared a world. Moses and Edom do not. The passion Moses feels for Miriam is inversely correlated to the degree to which Edom simply doesn’t care. That is the meaning of brother. Moses learns the vital teaching of moral particularism from his inability to find solidarity and hospitality amongst his distant cousins.

Shabbat Shalom,

Zohar Atkins @ Etz Hasadeh

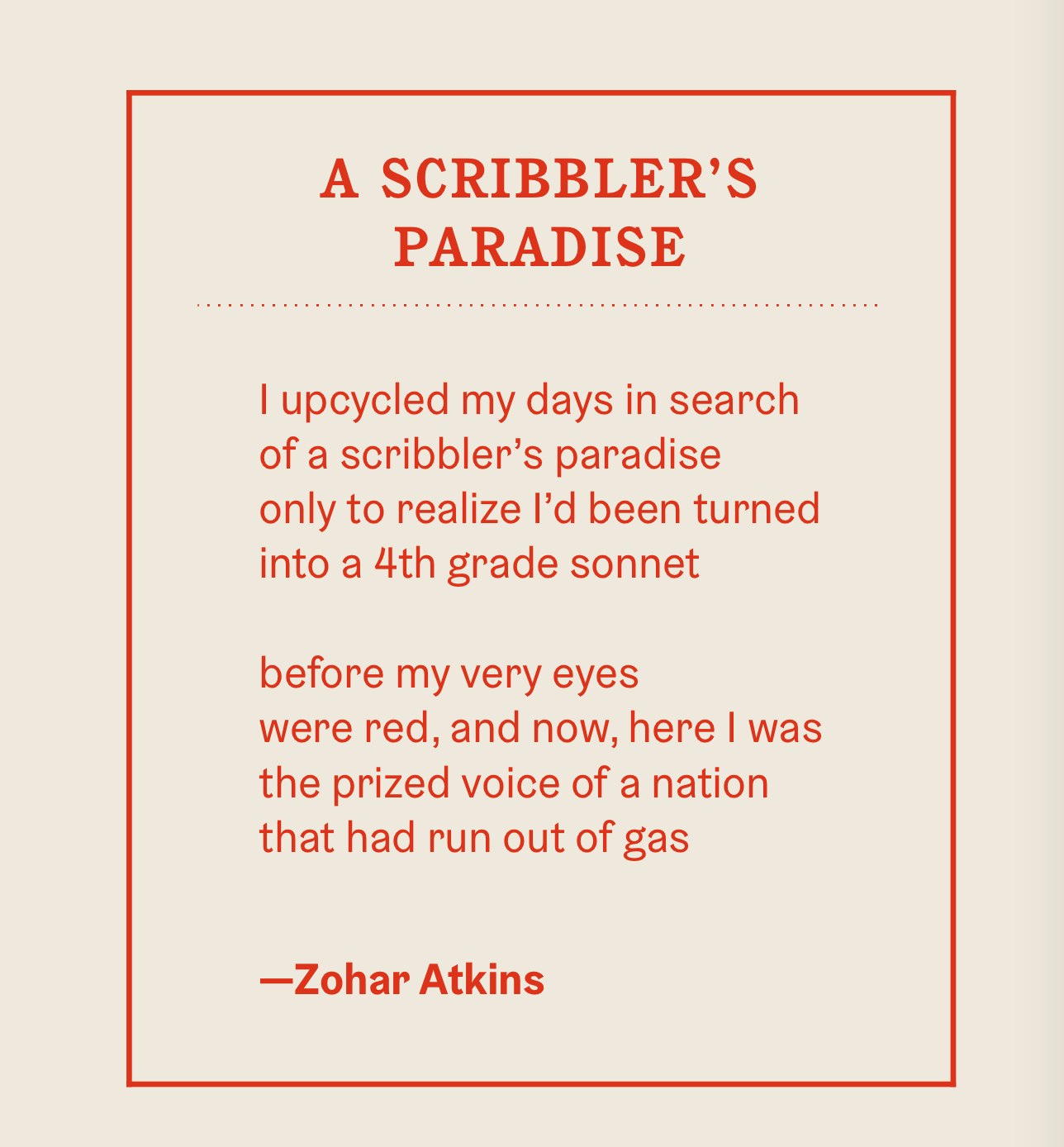

P.S.—Happy to share some new doggerel in Tablet