When I, in turn, have been hostile to them and have removed them into the land of their enemies, then at last shall their obdurate heart humble itself, and they shall atone for their iniquity. Then will I remember My covenant with Jacob; I will remember also My covenant with Isaac, and also My covenant with Abraham; and I will remember the land. (Leviticus 26:41-42)

One may not exchange or substitute another for it, either good for bad, or bad for good; if one does substitute one animal for another, the thing vowed and its substitute shall both be holy. (Leviticus 27:10)

Parashat Bechukotai opens with a standard promise of blessing in exchange for obedience, curse in exchange for disobedience. What is less conventional is God’s promise at the end of the list of curses to “remember My covenant with Jacob…” That is, the promise of forgiveness after breach of contract. Of course, the curses read in ways that strike us moderns as violent, brutal, far from loving. Yet in a martial context, our focus should not be on the promise of consequences, but on the affirmation of an abiding love. Not that this makes it much better—and some scholars, following the lead of prophets like Hosea—liken the God-Israel relationship to an abusive one, in which love and violence are intermixed.

Nonetheless, I find comfort in the Torah’s juxtaposition of the first part of Bechukotai—the blessings and curses—with the second part, an injunction not to substitute out a designated sacrifice for one that seems better. The moment you have made something holy, you can’t make it unholy. You can add to holiness, but you can’t subtract from it. Why juxtapose this sacrificial rule with a macro-discussion of the covenant? The literary implication seems to be that just as we cannot take back our commitments, so God, likewise, cannot. Now that God has chosen Israel God is stuck with Israel. Or if there is an exit clause, it’s not one that can be activated simply on a whim. The threshold is extremely high, if it exists at all.

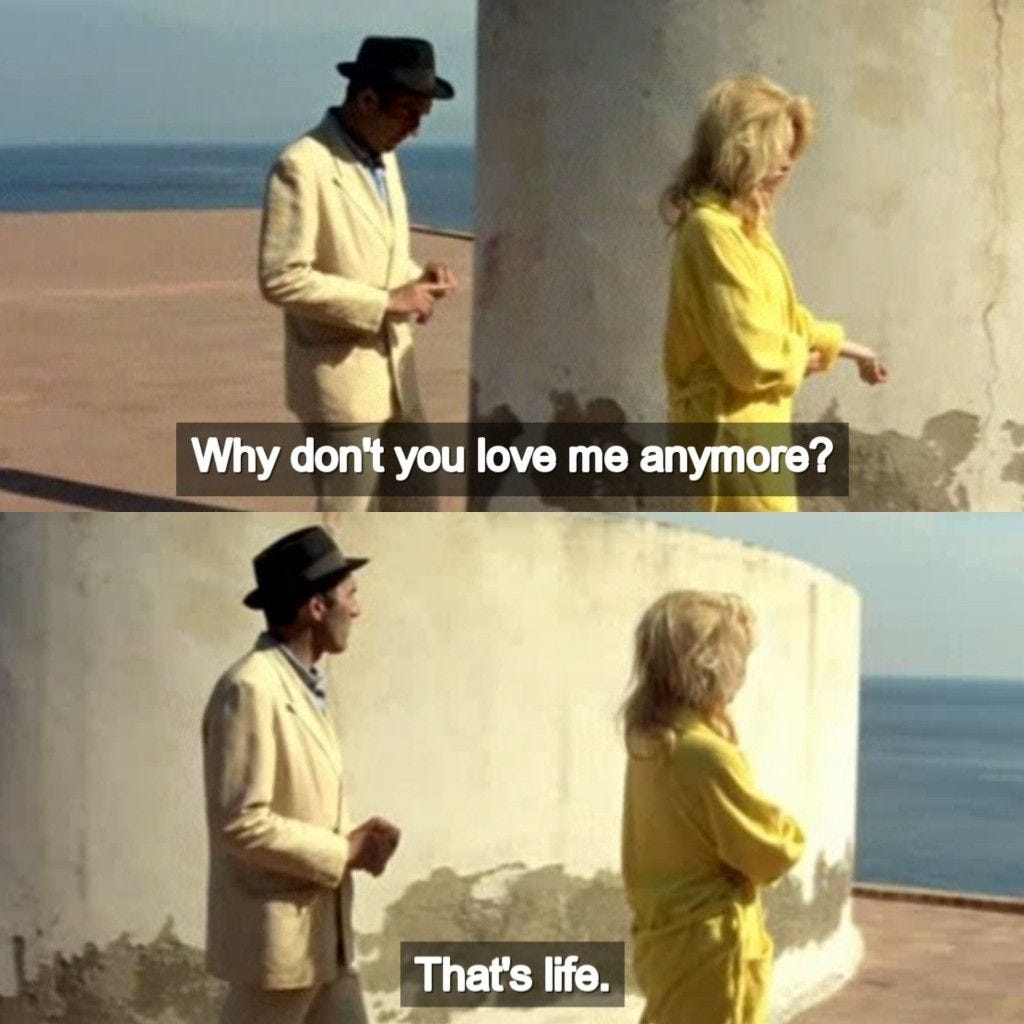

Can God make a stone to heavy for God to lift? Perhaps that stone is the covenant—which God has prohibited Godself from canceling. Why would God tie God’s hands in this way? Surely there must be some bounds on unconditional love? Some tripwire that turns love from boundless to conditional, as in Godard’s film, Contempt, which opens with an expression of total love yet ends with a reversal, following the form of a Greek tragedy.

But the ban on sacrificial substitution means one cannot “trade up,” and this applies to God, as well.

One hypothesis I have is that God knows that conditional love will condemn God to a life, as it were, of continuous unhappiness. God tried conditional love with humanity and it led to the flood, to the near destruction of the world. God cannot keep committing and annulling commitment every time a disappointment comes up. So, the move from Noah to Abraham, and then from Genesis to Exodus, and then Exodus to subsequent books is a move from conditional commitment to unconditional commitment, from love which is earned to love which can withstand bitter disappointment. Where normally, we think of blessing and curse as verdicts on a relationship, the subversive point of Bechukotai is that neither blessing nor curse can add to or subtract form the relationship itself.

The sages struggle with the idea of a covenant that Israel does not freely choose, imagining that God lifted the mountain over the heads of the people and threatened them with death if they did not accept the Torah. But that coercive original moment is a two-way street, as it also binds God. God, too, has a mountain over God’s head, and must attach Godself to a people—too humanity—come what may. We hope that one day that relationship can be chosen, voluntary, spontaneous. And Purim marks this moment in the Jewish calendar. But the core point of Bechukotai, which we read on the cusp of Shavuot, is that it is not only the people who say “naaseh v’nishma,” we “will do and then we will understand,” but also God.

Covenant comes not to end a difference in will or perspective between God and humanity, but to relieve divine and human loneliness. Neither blessing for obedience nor curse for disobedience will absolve either party of the burden of its existential aloneness. “It’s lonely at the top”—for God. None can know or share the divine point of view. But its lonelier, still, without the attempt to share that point of view. And so Revelation is an choice—not to share content, not to command loyalty—but to be with. This is the true blessing of creation and the one that historical circumstance cannot obliterate. The one who makes the wonders of world also seeks to accompany and be accompanied by creation.

Shabbat Shalom,

Zohar Atkins @ Etz Hasadeh

P.S.—Happy to share my new essay on the fool in Jewish thought for Ayin.