Pharaoh asked Jacob, “How many are the years of your life?” And Jacob answered Pharaoh, “The years of my sojourn are one hundred and thirty. Few and hard have been the years of my life, nor do they come up to the life spans of my fathers during their sojourns.” (Genesis 47:8-9)

I know no reason for this comment by our aged patriarch. Is it ethical for a person to complain to the king? And what sense is there in saying, and they have not attained unto the days of the years of the life of my fathers? He may yet possibly attain them and live even longer than they did! It appears to me that our father Jacob had turned gray, and he appeared very old. Pharaoh wondered about his age, for most people of his time did not live very long as the lifespan of mankind had already been shortened. He therefore asked him, “How many are the days of the years of thy life, as I have not seen a man as aged as you in my entire kingdom?” Then Jacob answered that he was one hundred and thirty years of age, and that he should not wonder at the years he had lived for they are few when compared with the lifespans of his fathers who had lived longer. However, on account of their having been hard years of toil and groaning, he had turned gray and he appeared extremely old. (Nachmanides on Genesis 47:8-9)

“Concerning your question how many years old am I, I must confess that I am relatively young in years, and I have certainly not benefited from any life-extending drugs or herbs; on the contrary, I have experienced enough troubles to hasten my old age and my death. Years during which a person is beset with major problems do not even count as ‘years of his life.’ But if you want to know how many years I have been sojourning on this planet, I am 130 years old.” (Seforno on Genesis 47:8-9)

An odd exchange occurs in this week’s parashah, Vayigash (Gen. 44:18-47:27), between Jacob and Pharaoh. Jacob comes down to Egypt to meet his long lost son, Joseph, and is introduced to Joseph’s boss, the most powerful man in the world, Pharaoh. Why does Pharaoh ask Jacob how old he is? This is the only question he asks him. And why is Jacob’s response so intense, at once cryptic, convoluted and TMI. Does the great world leader really want to know how Jacob, the shepherd, feels about his aging?

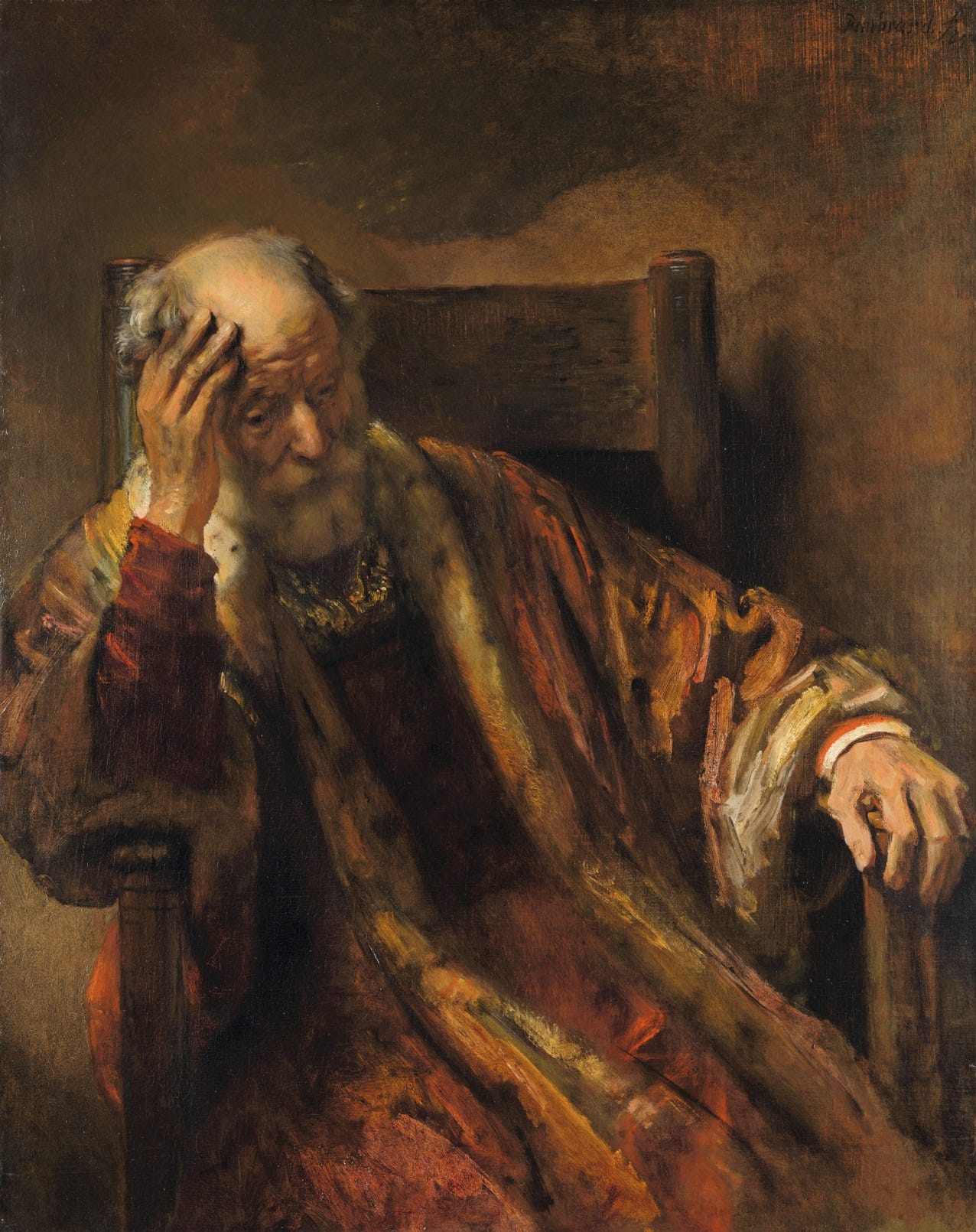

The classical commentators help contextualize the scene. In their rendering, Pharaoh is awe-struck at the spectacle of Jacob who looks older than anyone he has ever seen. Jacob, by contrast, measures himself against his father and grandfather, both of whom lived longer than him, and apparently were in a lot better shape. Jacob isn’t complaining that his life has been bitter, he’s explaining to Pharaoh why he looks so old.

Of course, there’s a tremendous irony and gravity to the moment the strong man and the weak man meet, a kind of symbolism of Jewish history, Jacob being a stand-in for the Jewish people as a whole. What is the greater feat, current power and strength, or a remarkable endurance, a longevity marked by battle-scars and doubt? Rashi says that Jacob is telling Pharaoh his life has been an unhappy one. Meanwhile, we can surmise, Pharaoh looks after himself, and has a great health and wellness budget. Still, the fact remains, in Pharaoh’s eyes, Jacob has achieved something that Egyptian civilization has not. The civilization that will later enslave Jacob’s descendants knows how to seize the day, but not how to hang in for tomorrow. It is Joseph, who comes from Jacob, that teaches the Egyptians the lesson of storage and investment, of having the abundance of fat years to call in the lean years.

In the subtle exchange, Jacob evinces something Pharaoh wants or wants to understand, but cannot. Perhaps it is connected to being a shepherd, a wanderer. The text tells us that the Egyptians find shepherding abhorrent, which is the reason the Israelites are afforded the pasture land of Goshen. Jacob does not say the years of his life have been 130, but the years of his sojourn. A shepherd and wanderer, he doesn’t have the kind of coherent unity of a life that one might find staying in one place. And yet, it seems, the nimbleness of the wanderer is connected to his longevity, a mystery the civilization builders, with their impressive pyramid-tombs and chemical innovations can’t fathom.

But should Pharaoh envy Jacob? According to Jacob—assuming he isn’t just being tactful—a long life in itself is hardly an accomplishment. In fact, Jacob proclaims a few verses before: “Now I can die, having seen for myself that you [Joseph] are still alive” (46:30). Jacob says this 17 years before he dies. He seems disinterested in living for life’s sake, and more interested in living for a sense of mission (and closure), which he thinks he has already achieved by the time he meets Pharaoh.

In Jacob’s tragic self-conception, he has spent most of his years in doubt, on the run. Recall that he was cheated out of marrying Rachel, postponing his marriage 7 years. Once Joseph was sold into slavery, Jacob—according to the Midrash—fell into a despondent state, imagining that he had failed in his mission. Jacob didn’t experience his life, or most of it, as a blessing. And so we have in the exchange between Pharaoh and Jacob a kind of personified debate: Is it better to live a long, but qualitatively poor life, or a shorter one that one might call good or happy?

I take the Torah’s answer to be that, at least in Jacob’s case, a long life, if an unhappy one, is better. Not because more years are better, but because our own self-evaluation cannot be the only metric by which we judge the worthiness and goodness of our own lives. Aristotle believed the good life was one of thriving. But even if Jacob didn’t thrive, he survived, and this was meaningful, at minimum because it allowed for the possibility of thriving in future moments. Jacob can’t renounce his life, because in doing so, he would be renouncing the moment on which the Book of Genesis ends, the moment in which he blesses his children and grandchildren. Pharaoh beholds the blessing in Jacob that Jacob doesn’t behold in himself, the blessing of another day, the blessing of continuity, the blessing of intergenerational gathering. Long and bitter have been many of the days of Jewish history, but we’re still here. Where is Pharaoh? Gone with the fat years. The lean shepherds who have roamed with the times have endured. Can one really be cheated of one’s time? One would need some quantum accounting to know for sure.

As Jacob descends to Egypt, God tells him, “Fear not to go down to Egypt, for I will make you there into a great nation” (46:3). Arguably, Jacob isn’t afraid he will become a great nation. He’s afraid of the price he will have to pay for becoming great, afraid of the oppression out of which the great nation will be forged. Loaded in God’s instruction, “Do not fear,” is a deeper lesson for Jacob and for us. How much time do we lose, how much of the days of our sojourn do we squander in fear? Granted, fear is inevitable, granted fear is sometimes rational and warranted, what would our lives be like if we cultivated a greater sense of faith and trust? This is very difficult, in general, and all the more so in trying times. Jacob lives an exemplary life simply by having the grit to live another day, even on those days when he feels poor for the task. But the higher life is one in which we are present to life as it is, not allowing our noisy minds to take us hostage. If we live with noisy minds, then 130 years can go by and what will we have to show for it? We will have beautiful children and grandchildren, and yet when the king says, “How are you?” we’ll be compelled to say, “Few and hard have been the days of my life.”

In his answer to Pharaoh, Jacob measures himself against his ancestors, and comes up short. Jacob feels a burden that Abraham did not. This is the burden of being a bridge, a successor, an interpreter rather than a founder or originator. His fathers are told not to go to Egypt. Now, Jacob is being told to go to Egypt. He can’t look to the past to provide the paradigm for his own life. This is a recipe for feeling like a failure. But each journey demands differently. Just as Cain should not have compared himself to Abel and Joseph’s brothers should not have compared themselves to Joseph, Jacob should not compare himself to Abraham and Isaac. This being the case, Jacob’s mission is most difficult, for while Abraham is the one who walks away from evil to do a new thing, Jacob is the one who must take his family into the belly of the beast, allowing his descendants to be enslaved.

God’s blessing in Genesis has always had two parts: a part promising suffering and a part promising redemption. Jacob is closest to the promise of suffering. He cannot see, or cannot always see, the redemption, in his anguish. But his journey is the bravest. For it is relatively easy to have faith when the cows are fat. Who can hold onto the memory and promise of blessing in times of famine? The hoary head of Jacob is a rebuke to every Pharaoh who thinks life is only about youth and happiness. It is the line-marked face of tradition reminding today’s disruptors that endurance always has the last word against novelty.

Shabbat Shalom,

Zohar Atkins @ Etz Hasadeh

P.S.—If you appreciate this work and feel moved to support it, you can make a tax deductible donation here and/or share this on social media. You may also enjoy my philosophy newsletter, What is Called Thinking?

What is the connection here, if any, to the doctrine of pikuach nefesh? There seems some affinity of this idea of endurance to the idea that you may-- sometimes even must-- suspend other principles of good conduct in order to help others to endure.