Be Here Soon

Once when Jacob was cooking a stew, Esav came in from the open, exhausted. And Esau said to Jacob, “Give me some of that red stuff to gulp down, for I am famished”—which is why he was named Edom. Jacob said, “Sell me your birthright as of today (lit. sell it to me as the day [k’yom]).” And Esau said, “I am going to die so what use is my birthright to me?” But Jacob said, “Swear to me as of today (lit. as the day, [k’yom]).” So he swore to him, and sold his birthright to Jacob. Jacob then gave Esav bread and lentil stew; he ate and drank, and he rose and went away. Thus did Esav spurn the birthright. (Genesis 25:29-35)

“Sell to me as of today!”—Jacob refers to the value of Esav’s birthright as of that day, and offers to pay that price. Seeing that the value is completely potential, Esau not knowing if Jacob will outlive him or will outlive his father, the price must surely be minimal. In either of those two events the birthright would be completely without any value. (Daat Z’kenim on Gen. 25:31)

“Be here now.” “Be present.” “There is only this moment.” These are common new age maxims whose superficial and commercialized use does not negate the fact that they are profound, challenging, and transformative charges.

With the exception of monastics, it’s true that most of us most of the time spend our time rehearsing the past and/or anticipating (worrying about) the future. It’s also true that we would be happier and more fun to be around if we spent less time in our heads. Thus, Shabbat and holidays, life-cycle celebrations and periods of mourning, offer us a chance to take a break from a mundane way of being that Heidegger calls “being ahead of ourselves” and to remember life itself.

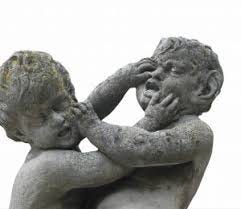

Yet, presentism can become solipsistic and self-centered, since it privileges my own experience now over and above any other moments and perspectives in the past and future. In this week’s Torah reading, Toldot (Gen. 25:19-26:5), Esav parts with his birthright for a bowl of lentils.

Now, you could say that he does this because he’s not mindful—that the negative lesson of his impulsivity yields something like “the slow food movement.” You could say that being more present allows us to care more deeply about the future, that Esav’s exhaustion was the opposite of contemplative, closer to the state of mind of the workaholic who rushes to the convenient store on a 20 minute lunch break to buy an energy drink (good for productivity in the present moment, but bad for health and wellness in the long-run). Whether you read it this way or not, it’s clear from how the tale ends that the emphasis is on Esav’s spurning of the birthright, not necessarily Jacob’s desert or legitimacy (it’s possible the brotherly transaction is illegitimate, possibly exploitative, and at the least, somewhat shady). The moral may be “don’t be like Esav” more than it is be like Jacob.

It’s ironic that Esav is tired from hunting all day! He must not have found any animals that day, or else, didn’t have time to cook what he had just killed. He’s a short-term thinker who enjoys a good find in the moment, but also, we can presume, doesn’t know how to manage his time, moving in volatile cycles from binge-eating to starvation and back. In archetypal fashion, Esav, “the knower of game” has brawn, but no sense of time beyond what he sees in the moment. Agricultural success, on which Jacob’s lentil dish depends, requires planning and long-term thinking. Jewish continuity, and not just Jewish, but all continuity of a tradition, requires that we think back to past generations and forward to future generations. A pure presentist can have no sense of and no need for tradition.

(Which brings us to a familiar Zen paradox: if every moment is perfect unto itself, why do I need the practice? Why sit for hours in silence watching my breath, if the moment in which I sit on the couch, surfing the internet and stuffing myself with ice cream is equally enlightened? Or in Jewish terms, if God is everywhere, why do I need the specific structures of a Temple or calendar or Jewish observance?)

G.K. Chesterton calls tradition “the democracy of the dead,” implying that those without tradition impose their will onto their ancestors like despots on their subjects. We can add that tradition, at its best, is also a democracy of the coming ones, the unborn (a point made by the Jewish philosopher, Hans Jonas) in that it asks us to become responsible for transmitting and sustaining it with future generations in mind. Esav, who takes the tasty dish now, and who believes that meaning ends with his death, is unfit to become a bestower of (Jewish) tradition.

The Da’at Z’kenim (a compendium of 12-13th century Franco-German commentaries) parses the birthright almost as a kind of complex financial instrument which has only speculative (and uncertain) value in the present, but might mature in value over time (like a stock, bond, or option). Thought through this lens, Jacob’s takes advantage of Esav’s ignorance about the future and pursues what Nassim Taleb calls “cheap optionality.” According to the Talmud (see for example, Kiddushin 63a), transactions that are contingent on something happening in the future are usually forbidden, according to the principle that one cannot buy or sell something that doesn’t (yet) exist (Jewish law has work-arounds without which much in modern economics would be off limits, including using cash). Viewed Talmudically, it’s possible that Esav’s intuition to take the lentils and spurn the birthright is so natural and so common that we need laws to protect him—and us—from throwing our futures away.

In context, Esav’s claim that he is going to die sounds melodramatic and hyperbolic. Yet, he’s literally right, opening the text to a double reading. Depending on our sense of our time horizon, we may balance the present differently against the future. On Yom Kippur, we explicitly cultivate an awareness of our mortality and fragility to gain a greater sense of responsibility and gravitas for how we live. But Yom Kippur is only one day a year and no matter what we commit to on the meditation retreat, life always when we return.

So, should we be more or less present?

Yes.

Pirkei Avot (4:17) teaches, “More precious is one hour in repentance and good deeds in this world, than all the life of the world to come; And more precious is one hour of the tranquility of the world to come, than all the life of this world.”

Paradoxically and dialectically, Jewish tradition affirms the importance of now and the importance of something other than now, something later. Still, the emphasis seems to be on the now.

If so, Esav’s error was not necessarily that he sought present satisfaction rather than future reward. The error was less a formal one than a content one. We should ask ourselves, from Esau’s example, what would be our bowl of lentils that is worth giving up a birthright for? (I recall a Hasidic story about a Rebbe who sought to give up his place in the world to come in exchange for God helping one of his congregants.) If Esav represents the so-called “Fierce urgency of now,” the ridiculousness of the scene is that he has self-inflicted (through poor planning) a situation in which his urgency is for survival, rather than thriving, generosity, or purposeful living.

Esav and Jacob are twins. Presentism comes out first, with an orientation to the future coming out second holding its heal. Children know only the moment, and have to be habituated into memory and expectation (I think). Presentism is the b’chor, the first-born and the choicest. A sense of the future, and a sense of tradition, though, are where we find bracha, blessing (a word-play on the word b’chor). Without concern for the future, and without concern for others, we can’t be optimally and peacefully present.

Rebecca finds herself in physical (and existential) agony, carrying twins with such different natures in her womb. Why is this me? she asks. But that agony is the human condition and can have no settled answer. We are beings who carry both the demands of the present and the future within us. The prophetic response she receives is also opaque—“the younger the older shall serve”—which means that either one can and will serve the other.

Archetypally, Esav is Rome and secular society, with its short-sighted focus on the now. Jacob/Israel is a religious world ruled by a sense of sacred, cyclical time and what is enduring. Yet, we need both perspectives, conflictual as they are. In reality, there is neither a pure Jacob nor a pure Esau. All societies, groups, and individuals, must find their own tentative balance between “now is all we have” and “see you tomorrow.”

Adieu, Shabbat Shalom, and Chodesh Tov,

Zohar Atkins @Etz Hasadeh

P.S.—If you enjoy these weekly blasts, you may enjoy my daily question newsletter What Is Called Thinking?

Etz Hasadeh is a Center for Existential Torah Study based in NYC.

About the name: Deuteronomy 20:19 teaches that when one conquers territory, one should not cut down the trees, because trees, unlike people, cannot run way. Read spiritually, the image-concept of the “tree of the field” represents that which we must preserve in the face of great cultural, political, and technological upheaval and transformation. As the world becomes more and more modernized, it becomes even more necessary to secure our connection to the wisdom of the ancient past and to ways of being that give our lives irreducible meaning.

Etz Hasadeh is fiscally sponsored by Jewish Creativity International, a 501c3 organization. If you appreciate this work and feel moved to support it, you can send a tax deductible donation by check to Jewish Creativity International with “Etz Hasadeh” in the memo. Address: Jewish Creativity International, Attn.: [Etz Hasadeh], 2472 Broadway, #331, New York, NY 10025